The National Socialist German Workers' Party (abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known in English as the Nazi Party, was a political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945. Its predecessor, the German Workers' Party (DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The term Nazi is German and stems from Nationalsozialist, due to the pronunciation of Latin -tion- as -tsion- in German (rather than -shon- as it is in English), with German Z being pronounced as 'ts'.

To maintain the supposed purity and strength of a postulated "Aryan master race", the Nazis sought to exterminate or impose exclusionary segregation upon "degenerate" and "asocial" groups that included: Jews, homosexuals, Romani, blacks, the physically andmentally handicapped, Jehovah's Witnesses and political opponents. The persecution reached its climax when the party-controlled German state organized the systematic murder of approximately six million Jews and five million people from the other targeted groups, in what has become known as the Holocaust.The party emerged from the German nationalist, racist and populist Freikorps paramilitary culture, which fought against the communist uprisings in post-World War I Germany.Advocacy of a form of socialism by right-wing figures and movements in Germany became common during and after World War I, influencing Nazism. Arthur Moeller van den Bruckof the Conservative Revolutionary movement coined the term "Third Reich", and advocated an ideology combining the nationalism of the right and the socialism of the left. Prominent Conservative Revolutionary member Oswald Spengler's conception of a "Prussian Socialism" influenced the Nazis. The party was created as a means to draw workers away from communism and into völkisch nationalism. Initially, Nazi political strategy focused on anti-big business, anti-bourgeois, and anti-capitalist rhetoric, although such aspects were later downplayed in order to gain the support of industrial entities, and in 1930s the party's focus shifted to antisemitic and anti-Marxist themes.

The party's leader since 1921, Adolf Hitler, was appointed Chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg in 1933. Hitler rapidly established a totalitarian regime known as the Third Reich. Following the defeat of the Third Reich at the conclusion of World War II in Europe, the party was "completely and finally abolished and declared to be illegal" by the Allied occupying powers.

Etymology

The term Nazi derives from the first two syllables of Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei(NSDAP, Nazi Party). The German term Nazi parallels the term Sozi (pronounced /zoːtsi/), an abbreviation of Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany). Members of the NSDAP referred to themselves as Nationalsozialisten (National Socialists), rarely as Nazis. In 1933, when Adolf Hitler assumed power of the German government, usage of the term Nazi diminished in Germany, although Austrian anti-Nazis continued to use the term as an insult.

History

Origins and early existence: 1918–1923

The party grew out of smaller political groups with a nationalist orientation that formed in the last years of World War I. In 1918, a league called the Freien Arbeiterausschuss für einen guten Frieden(Free Workers' Committee for a good Peace) was created in Bremen, Germany. On 7 March 1918, Anton Drexler, an avid German nationalist, formed a branch of this league in Munich called the "Committee of Independent Workmen". Drexler was a local locksmith in Munich who had been a member of the militarist Fatherland Party during World War I, and was bitterly opposed to the armistice of November 1918 and the revolutionary upheavals that followed. Drexler followed the typical views of militant nationalists of the day, such as opposing theTreaty of Versailles, having antisemitic, anti-monarchist and anti-Marxist views, as well as believing in the superiority of Germans whom nationalists claimed to be part of the Aryan "master race" (Herrenvolk), but he also accused international capitalism of being a Jewish-dominated movement and denounced capitalists for war profiteering in World War I. Drexler saw the situation of political violence and instability in Germany as the result of the new Weimar Republic being out-of-touch with the masses, especially the lower classes.Drexler emphasized the need for a synthesis of völkisch nationalism with a form of economic socialism, in order to create a popular nationalist-oriented workers' movement that could challenge the rise of Communism and internationalist politics. These were all well-known themes popular with various Weimar paramilitary groups such as the Freikorps.

Though very small, Drexler's movement did receive attention and support from some influential figures. Drexler's supporter Dietrich Eckhart brought military figure Count Felix Graf von Bothmer, a prominent supporter of the concept of "national socialism", to address the movement. Later in 1918, Karl Harrer(a journalist and member of the Thule Society), along with Drexler and several others formed thePolitischer Arbeiterzirkel (Political Workers' Circle). The members met periodically for discussions with themes of nationalism and racism directed against the Jews. In December 1918, Drexler decided a new political party should be formed based on the political principles which he endorsed by combining his Committee of Independent Workmen with the Political Workers' Circle.

On 5 January 1919, Drexler created a new political party and proposed it be named the "German Socialist Worker's Party", but Harrer objected to the term "socialist"; the issue was settled by removing the term and the party was named the German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP). To ease concerns among potential middle-class supporters, Drexler made clear that unlike Marxists, the party supported the middle-class, and that the party's socialist policy was meant to give social welfare to German citizens deemed part of the Aryan race. They became one of many völkisch movements that existed in Germany at the time. Like other völkisch groups, the DAP advocated the belief that through profit-sharing instead of socialisation Germany should become a unified "national community" (Volksgemeinschaft) rather than a society divided along class and party lines. This ideology was explicitly antisemitic. As early as 1920, the party was raising money by selling a tobacco called Anti-Semit.

From the outset, the DAP was opposed to non-nationalist political movements, especially on the left, including the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the newly formed Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Members of the DAP saw themselves as fighting against "Bolshevism" and anyone considered a part of or aiding so-called "international Jewry". The DAP was deeply opposed to theVersailles Treaty. The DAP did not attempt to make itself public, and meetings were kept in relative secrecy, with public speakers discussing what they thought of Germany's present state of affairs, or writing to like-minded societies in Northern Germany.

The DAP was a comparatively small group with fewer than 60 members. Nevertheless, it attracted the attention of the German authorities, who were suspicious of any organisation that appeared to have subversive tendencies. In July 1919 while stationed in Munich, army Gefreiter Adolf Hitler was appointed a Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of the Reichswehr (army) by the head of press and propaganda in the Bavarian section, Captain Mayr. Hitler's assignment was to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the DAP. While attending a party meeting on 12 September 1919, Hitler became involved in a heated argument with a visitor, Professor Baumann, who questioned the soundness of Gottfried Feder's arguments against capitalism and proposed that Bavaria should break away from Prussia and found a new South German nation with Austria. In vehemently attacking the man's arguments, he made an impression on the other party members with his oratory skills and, according to Hitler, the "professor" left the hall acknowledging unequivocal defeat. According toAugust Kubizek, Drexler was so impressed that he whispered to a neighbour, "My he's got a gift of the gab. We could use him."Drexler invited him to join, and Hitler accepted. In less than a week, Hitler received a postcard from Drexler stating he had officially been accepted as a DAP member. Among the party's earlier members were Ernst Röhm of the Army's District Command VII; well-to-do journalist Dietrich Eckart; then University of Munich student Rudolf Hess; Freikorps soldier Hans Frank; and Alfred Rosenberg, often credited as the philosopher of the movement. All were later prominent in the Nazi regime.

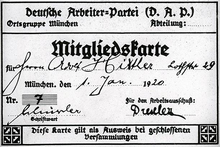

Hitler became the DAP's 55th member and received the number 555, as the DAP added '500' to every member's number to exaggerate the party's strength. He later claimed to be the seventh party member (he was in fact the seventh executive member of the party's central committee; he would later wear the Golden Party Badge number one). Hitler's first speech was held in the Hofbräukeller, where he spoke in front of 111 people as the second speaker of the evening. Hitler later declared that this was when he realised he could really "make a good speech". At first Hitler only spoke to relatively small groups, but his considerable oratory and propaganda skills were appreciated by the party leadership. With the support of Anton Drexler, Hitler became chief of propaganda for the party in early 1920. Hitler began to make the party more public, and he organised their biggest meeting yet of 2,000 people, on 24 February 1920 in the Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München. Such was the significance of this particular move in publicity that Harrer resigned from the party in disagreement. It was in this speech that Hitler, for the first time, enunciated the twenty-five points of the German Worker's Party's manifesto that had been drawn up by Drexler, Feder, and Hitler. Through these points he gave the organisation a much bolder stratagem with a clear foreign policy (abrogation of The Treaty of Versailles, a Greater Germany, Eastern expansion, exclusion of Jews from citizenship), and among his specific points were: confiscation of war profits, abolition of unearned incomes, the State to share profits of land, and land for national needs to be taken away without compensation. In general, the manifesto was antisemitic, anti-capitalist, anti-democratic, anti-Marxist, and anti-liberal. To increase its appeal to larger segments of the population, in February 1920 the DAP changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party – NSDAP). That year, the Nazi Party officially announced that only persons of "pure Aryan descent [rein arischer abkunft]" could become party members; if the person had a spouse, they also had to be a "racially pure" Aryan. Party members could not be related either directly or indirectly to a so-called "non-Aryan".

Hitler quickly became the party's most active orator. Hitler's considerable oratory and propaganda skills were appreciated by the party leadership as crowds began to flock to hear his speeches. Hitler always spoke about the same subjects: the Treaty of Versailles andthe Jewish question. This deliberate technique and effective publicising of the party contributed significantly to his early success,about which a contemporary poster wrote 'Since Herr Hitler is a brilliant speaker, we can hold out the prospect of an extremely exciting evening'. Over the following months, the party continued to attract new members, while remaining too small to have any real significance in German politics. By the end of the year, party membership was recorded at 2,000. Many of whom Hitler and Röhm had brought into the party personally, or for whom Hitler's oratory had been their reason for joining.

Hitler's talent as an orator, and his ability to draw new members, combined with his characteristic ruthlessness, soon made him the dominant figure. However, while Hitler was on a fundraising trip to Berlin in June 1921, a mutiny broke out within the Nazi Party in Munich. Members of its executive committee, some of whom considered Hitler to be too overbearing, wanted to merge with the rivalGerman Socialist Party (DSP). Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July and angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that his resignation would mean the end of the party. Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich. The committee agreed, and he rejoined the party on 26 July as member 3,680. He still faced some opposition within the NSDAP: Opponents of Hitler had Hermann Esser expelled from the party and they printed 3,000 copies of a pamphlet attacking Hitler as a traitor to the party. In the following days, Hitler spoke to several packed houses and defended himself and Esser, to thunderous applause.

Hitler was formally elected party chairman on 28 July 1921, with only one opposing vote. The committee was dissolved, and Hitler was granted nearly absolute powers as the party's sole leader. This was a post he would hold for the remainder of his life. Hitler soon acquired the title Führer ("leader") and, after a series of sharp internal conflicts, it was accepted that the party would be governed by theFührerprinzip ("leader principle"). Under this principle, the party was a highly centralized entity that functioned strictly from the top down, with Hitler at the apex as the party's absolute leader. Hitler at this time saw the party as a revolutionary organization, whose aim was the overthrow of the Weimar Republic, which he saw as controlled by the socialists, Jews and the "November criminals" who had betrayed the German soldiers in 1918. The SA ("storm troopers", also known as "Brownshirts") were founded as a party militia in 1921, and began violent attacks on other parties.

For Hitler, the twin goals of the party were always German nationalist expansionism and antisemitism. These two goals were fused in his mind by his belief that Germany's external enemies – Britain, France and the Soviet Union – were controlled by the Jews, and that Germany's future wars of national expansion would necessarily entail a war against the Jews. For Hitler and his principal lieutenants, national and racial issues were always dominant. This was symbolised by the adoption as the party emblem of the swastika orHakenkreuz, at the time widely used in the western world. In German nationalist circles, the swastika was considered a symbol of an "Aryan race"; it symbolized the replacement of the Christian Cross with allegiance to a National Socialist State.

During 1921 and 1922, the Nazi Party grew significantly, partly through Hitler's oratorical skills, partly through the SA's appeal to unemployed young men, and partly because there was a backlash against socialist and liberal politics in Bavaria as Germany's economic problems deepened and the weakness of the Weimar regime became apparent. The party recruited former World War I soldiers, to whom Hitler as a decorated frontline veteran could particularly appeal, as well as small businessmen and disaffected former members of rival parties. Nazi rallies were often held in beer halls, where downtrodden men could get free beer. The Hitler Youth was formed for the children of party members, although it remained small until the late 1920s. The party also formed groups in other parts of Germany.Julius Streicher in Nuremberg was an early recruit, and became editor of the racist magazine Der Stürmer. Others to join the party around this time were WW I flying ace Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler. In December 1920 the party acquired a newspaper, theVölkischer Beobachter, of which NSDAP ideological chief Alfred Rosenberg became editor.

In 1922, a party with remarkably similar policies and objectives came into power in Italy, the National Fascist Party under the leadership of the charismatic Benito Mussolini. The Fascists, like the Nazis, promoted a national rebirth of their country; opposed communism and liberalism; appealed to the working-class; opposed the Treaty of Versailles; and advocated the territorial expansion of their country. The Italian Fascists used a straight-armed Roman salute and wore black-shirted uniforms. Hitler was inspired by Mussolini and the Fascists, borrowing their use of the straight-armed salute as a Nazi salute. When the Fascists came to power in 1922 in Italy through their coup attempt called the "March on Rome", Hitler began planning his own coup which would materialize one year later.

In January 1923, France occupied the Ruhr industrial region as a result of Germany's failure to meet its reparations payments. This led to economic chaos, the resignation of Wilhelm Cuno's government, and an attempt by the German Communist Party (KPD) to stage a revolution. The reaction to these events was an upsurge of nationalist sentiment. Nazi Party membership grew sharply, to about 20,000. By November, Hitler had decided that the time was right for an attempt to seize power in Munich, in the hope that theReichswehr (the post-war German military) would mutiny against the Berlin government and join his revolt. In this he was influenced by former General Erich Ludendorff, who had become a supporter—though not a member—of the Nazis.

On the night of 8 November, the Nazis used a patriotic rally in a Munich beer hall to launch an attempted putsch (coup d'état). This so-called Beer Hall Putsch attempt failed almost at once when the local Reichswehr commanders refused to support it. On the morning of 9 November the Nazis staged a march of about 2,000 supporters through Munich in an attempt to rally support. Troops opened fire, and 16 Nazis were killed. Hitler, Ludendorff and a number of others were arrested, and were tried for treason in March 1924. Hitler and his associates were given very lenient prison sentences. While Hitler was in prison, he wrote his semi-autobiographical political manifestoMein Kampf ("My Struggle").

The Nazi Party was banned, though with support of the nationalist Völkisch-Social Bloc (Völkisch-Sozialer Block), continued to operate under the name of the "German Party" (Deutsche Partei or DP) from 1924 to 1925. The Nazis failed to remain unified in the German Party, as in the north, the right-wing Volkish nationalist supporters of the Nazis moved to the new German Völkisch Freedom Party, leaving the north's left-wing Nazi members, such as Joseph Goebbels retaining support for the party.

Ascension and consolidation

Hitler in Mein Kampf directly attacked both left-wing and right-wing politics in Germany.However, a majority of scholars identify Nazism in practice as being a far-right form of politics.When asked in an interview whether he and the Nazis were "bourgeois right-wing" as alleged by their opponents, Hitler responded that Nazism was not exclusively for any class, and indicated that it favoured neither the left nor the right, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps", stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism".

The votes that the Nazis received in the 1932 elections established the Nazi Party as the largest parliamentary faction of the Weimar Republic government. Adolf Hitler was appointed as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933.

The Reichstag fire on 27 February 1933 gave Hitler a raison d'état for suppressing his political opponents. The following day, 28 February, he persuaded Weimar Republic President Paul von Hindenburg to issue the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended most civil liberties. On 23 March, the Reichstag passed the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave the cabinet the right to enact laws without the consent of the Reichstag. In effect, this gave Hitler dictatorial powers. Now possessing virtually absolute power, the Nazis established totalitarian control; they abolished labour unions and political parties, and imprisoned their political opponents, first at wilde Lager, improvised camps, then in concentration camps. Nazism had been established, yet theReichswehr remained impartial: Nazi power over Germany remained virtual, not absolute.

Party composition

Command structure

Top leadership

At the top of the Nazi Party was the party chairman ("Der Führer"), who held absolute power and full command over the party. All other party offices were subordinate to his position and had to depend on his instructions. In 1934, Hitler founded a separate body for the chairman, Chancellery of the Führer, with its own sub-units.

Below the Führer's chancellery was first the "Staff of the Deputy Führer" (headed by Rudolf Hess from 21 April 1933 to 10 May 1941) and then the "Party Chancellery" (Parteikanzlei) headed by Martin Bormann.

Reichsleiter

Directly subjected to the Führer were the Reichsleiter ("Reich Leader(s)"—the singular and plural forms are identical in German), whose number was gradually increased to eighteen. They held power and influence comparable to the Reich Ministers' in Hitler's Cabinet. The eighteen Reichsleiter formed the "Reich Leadership of the Nazi Party" (Reichsleitung der NSDAP), which was established at the so-called Brown House, in Munich. Unlike a Gauleiter, a Reichsleiter did not have individual geographic areas under their command, but were responsible for specific spheres of interest.

Political leadership corps

The political leadership corps of the Nazi Party were those persons who were most often associated as being "Nazis" in the stereotypical sense of the word, as it was these individuals who wore brown paramilitary Nazi uniforms, enforced Nazi doctrine, and ran local government affairs in accordance with instructions from the Nazi Party.

The political leadership corps encompassed a vast array of paramilitary titles at the top of which were Gauleiter, who were Party leaders of large geographical areas. From the Gauleiters extended downwards through Nazi positions encompassing county, city, and town leaders, all of whom were unquestioned rulers in their particular areas and regions.

To the very end of its existence, the Nazi Party claimed to respect the traditional government of Germany and, to that end, local and state governments were allowed to exist side-by-side with regional Nazi leaders. However, by 1936, the local governments had lost nearly all power to their Nazi counterparts or were now controlled by persons who held both government and Nazi titles alike. This led to the continued existence of German titles such as Bürgermeister, as well as the existence of German state legislatures (Landesrat), but without any real power to speak of.

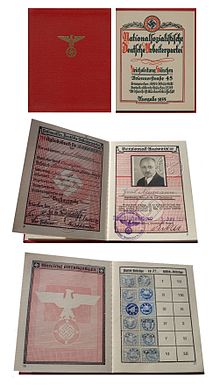

Ordinary members

The general Nazi Party membership were known by the title of Parteimitglieder. This generic term applied to any member of the Party who did not otherwise hold a political leadership position. Translated simply as "Party Member", the Parteimitglieder could (and did) hold positions in other Nazi groups, such as the SS or Sturmabteilung. The only insignia for the Parteimitglieder was a Nazi Party lapel-pin; Nazi Party members who held no leadership posts had no specific designated uniform. Such persons, however, often wore uniforms of other Nazi groups, uniforms of German government agencies, and could also serve in the German armed forces.

Membership

General membership

The general membership of the Nazi Party mainly consisted of the urban and rural lower middle classes. 7% belonged to the upper class, another 7% were peasants, 35% were industrial workers and 51% were what can be described as middle class. In early 1933, just before Hitler's appointment to the chancellorship, the party showed an under-representation of "workers", who made up 29.7% of the membership but 46.3% of German society. Conversely, white-collar employees (18.6% of members and 12% of Germans), the self-employed (19.8% of members and 9.6% of Germans), and civil servants (15.2% of members and 4.8% of the German population) had joined in proportions greater than their share of the general population. These members were affiliated with local branches of the party, of which there were 1,378 throughout the country in 1928. In 1932, the number had risen to 11,845, reflecting the party's growth in this period.

When it came to power in 1933, the Nazi Party had over 2 million members. In 1939, the membership total rose to 5.3 million with 81% being male and 19% being female. It continued to attract many more and by 1945 the party reached its peak of 8 million with 63% being male and 37% being female.

Military membership

Nazi members with military ambitions were encouraged to join the Waffen-SS, but a great number enlisted in the Wehrmacht and even more were drafted for service after World War II began. Early regulations required that all Wehrmacht members be non-political, and therefore any Nazi member joining in the 1930s was required to resign from the Nazi Party.

This regulation was soon waived, however, and there is ample evidence that full Nazi Party members served in the Wehrmacht in particular after the outbreak of World War II. The Wehrmacht Reserves also saw a high number of senior Nazis enlisting, with Reinhard Heydrich and Fritz Todt joining the Luftwaffe, as well as Karl Hanke who served in the army.

Student membership

In 1926, the NSDAP formed a special division to engage the student population, known as the National Socialist German Students' League (NSDStB). A group for university lecturers, the National Socialist German University Lecturers' League, (NSDDB) existed until July 1944.

Women membership

The National Socialist Women's League was the women's organization of the party. By 1938 it had approximately 2 million members.

Membership outside of Germany

Party members who lived outside of Germany were pooled into the Auslands-Organisation (NSDAP/AO, "Foreign Organization"). The organization was limited only to so-called "Imperial Germans"; "Ethnic Germans" (Volksdeutsche) who did not hold German citizenship were not permitted to join.

Under Beneš decree No. 16/1945 Coll., in case of citizens of Czechoslovakia, membership of NSDAP was punishable by 5–20 years of imprisonment.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

09:28

09:28

Planet Worldwide

Planet Worldwide

Posted in:

Posted in:

0 comments:

Post a Comment