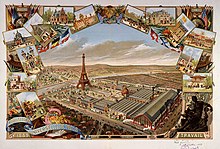

The Eiffel Tower (French: La Tour Eiffel,) is an iron lattice tower located on the Champ de Mars in Paris. It was named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower. Erected in 1889 as the entrance arch to the1889 World's Fair, it has become both a global cultural icon of France and one of the most recognizable structures in the world. The tower is the tallest structure in Parisand the most-visited paid monument in the world; 6.98 million people ascended it in 2011. The tower received its 250 millionth visitor in 2010.

The Eiffel Tower (French: La Tour Eiffel,) is an iron lattice tower located on the Champ de Mars in Paris. It was named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower. Erected in 1889 as the entrance arch to the1889 World's Fair, it has become both a global cultural icon of France and one of the most recognizable structures in the world. The tower is the tallest structure in Parisand the most-visited paid monument in the world; 6.98 million people ascended it in 2011. The tower received its 250 millionth visitor in 2010.

The tower is 324 metres (1,063 ft) tall about the same height as an 81-storey building. During its construction, the Eiffel Tower surpassed the Washington Monumentto assume the title of the tallest human-made structure in the world, a title it held for 41 years, until the Chrysler Building in New York City was built in 1930. Because of the addition of the antenna atop the Eiffel Tower in 1957, it is now taller than the Chrysler Building by 5.2 metres (17 ft). Not including broadcast antennae, it is the second-tallest structure in France, after the Millau Viaduct.

The tower has three levels for visitors, with restaurants on the first and second. The third level observatory's upper platform is 276 m (906 ft) above the ground, the highest accessible to the public in the European Union. Tickets can be purchased to ascend by stairs or lift (elevator) to the first and second levels. The climb from ground level to the first level is over 300 steps, as is the walk from the first to the second level. Although there are stairs to the third and highest level, these are usually closed to the public and it is generally only accessible by lift.

History

Origin

The design of the Eiffel Tower was originated by Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, two senior engineers who worked for the Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel, after discussion about a suitable centrepiece for the proposed 1889 Exposition Universelle, aWorld's Fair which would celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution. In May 1884 Koechlin, working at home, made an outline drawing of their scheme, described by him as "a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top, joined together by metal trusses at regular intervals".Initially Eiffel himself showed little enthusiasm, but he did sanction further study of the project, and the two engineers then asked Stephen Sauvestre, the head of company's architectural department, to contribute to the design. Sauvestre added decorative arches to the base, a glass pavilion to the first level, and other embellishments. This enhanced version gained Eiffel's support: he bought the rights to the patent on the design which Koechlin, Nougier, and Sauvestre had taken out, and the design was exhibited at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in the autumn of 1884 under the company name. On 30 March 1885 Eiffel presented a paper on the project to the Société des Ingiénieurs Civils; after discussing the technical problems and emphasising the practical uses of the tower, he finished his talk by saying that the tower would symbolise

"not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France's gratitude."

Little happened until the beginning of 1886, when Jules Grévy was re-elected as President andÉdouard Lockroy was appointed as Minister for Trade. A budget for the Exposition was passed and on 1 May Lockroy announced an alteration to the terms of the open competition which was being held for a centerpiece for the exposition, which effectively made the choice of Eiffel's design a foregone conclusion: all entries had to include a study for a 300 m (980 ft) four-sided metal tower on the Champ de Mars. On 12 May a commission was set up to examine Eiffel's scheme and its rivals and on 12 June it presented its decision, which was that all the proposals except Eiffel's were either impractical or insufficiently worked out. After some debate about the exact site for the tower, a contract was finally signed on 8 January 1887. This was signed by Eiffel acting in his own capacity rather than as the representative of his company, and granted him 1.5 million francs toward the construction costs: less than a quarter of the estimated 6.5 million francs. Eiffel was to receive all income from the commercial exploitation of the tower during the exhibition and for the following twenty years. Eiffel later established a separate company to manage the tower, putting up half the necessary capital himself.

Construction

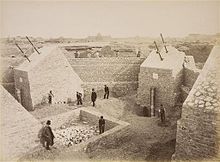

Work on the foundations started on 28 January 1887. Those for the east and south legs were straightforward, each leg resting on four 2 m (6.6 ft) concrete slabs, one for each of the principal girders of each leg but the other two, being closer to the river Seine, were more complicated: each slab needed two piles installed by using compressed-air caissons 15 m (49 ft) long and 6 m (20 ft) in diameter driven to a depth of 22 m (72 ft) to support the concrete slabs, which were 6 m (20 ft) thick. Each of these slabs supported a block built of limestone each with an inclined top to bear a supporting shoe for the ironwork. Each shoe was anchored into the stonework by a pair of bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long. The foundations were complete by 30 June and the erection of the ironwork began. The very visible work on-site was complemented by the enormous amount of exacting preparatory work that was entailed: the drawing office produced 1,700 general drawings and 3,629 detailed drawings of the 18,038 different parts needed. The task of drawing the components was complicated by the complex angles involved in the design and the degree of precision required: the position of rivet holes was specified to within 0.1 mm (0.04 in) and angles worked out to one second of arc. The finished components, some already riveted together into sub-assemblies, arrived on horse-drawn carts from the factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret and were first bolted together, the bolts being replaced by rivets as construction progressed. No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit it was sent back to the factory for alteration. In all there were 18,038 pieces joined by two and a half million rivets.

At first the legs were constructed as cantilevers but about halfway to the first level construction was paused in order to construct a substantial timber scaffold. This caused a renewal of the concerns about the structural soundness of the project, and sensational headlines such as "Eiffel Suicide!" and "Gustave Eiffel has gone mad: he has been confined in an Asylum" appeared in the popular press. At this stage a small "creeper" crane was installed in each leg, designed to move up the tower as construction progressed and making use of the guides for the lifts which were to be fitted in each leg. The critical stage of joining the four legs at the first level was complete by the end of March 1888. Although the metalwork had been prepared with the utmost precision, provision had been made to carry out small adjustments in order to precisely align the legs: hydraulic jacks were fitted to the shoes at the base of each leg, each capable of exerting a force of 800 tonnes, and in addition the legs had been intentionally constructed at a slightly steeper angle than necessary, being supported by sandboxes on the scaffold. Although construction involved 300 on-site employees, only one person died thanks to Eiffel's stringent safety precautions and use of movable stagings, guard-rails, and screens.

Lifts

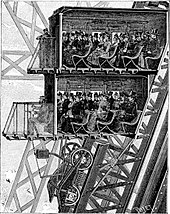

Equipping the Tower with adequate and safe passenger lifts was a major concern of the government commission overseeing the Exposition. Although some visitors could be expected to climb to the first or even the second stage, the main means of ascent clearly had to be lifts.

Constructing lifts to reach the first platform was relatively straightforward: the legs of the lower section were wide enough and so nearly straight that they could contain a straight track, and a contract was given to the French company Roux, Combaluzier and Lepape for two lifts to be fitted in the east and west legs. The lifts to the second problem presented a more complex problem, because a straight track was not possible. No French company was willing to undertake the work. The European branch of Otis Brothers & Company, submitted a proposal but this was rejected: the fair’s charter ruled out the use of any foreign material in the construction of the Tower. The deadline for bids was extended, but still no French companies put themselves forward, and eventually the contract was given to Otis in July 1887.

The original lifts from the second to the third floor were supplied by Léon Edoux. A pair of 81 m (266 ft) hydraulic rams were mounted on the second level, reaching nearly halfway up to the third level. One lift car was mounted on top of these rams, cables ran from the top of this car up to sheaves on the third level and then back down to a second car. Each car only travelled half the distance between the second and third levels and passengers were required to change lifts halfway by means of a short gangway. The ten-ton cars held 65 passengers each.

Inauguration and the 1889 Exposition

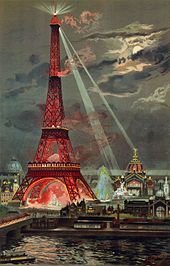

The main structural work was completed at the end of March 1889 and on the 31st Eiffel celebrated this by leading a group of government officials, accompanied by representatives of the press, to the top of the tower. Since the lifts were not yet in operation, the ascent was made by foot, and took over an hour, Eiffel frequently stopping to make explanations of various features. Most of the party chose to stop at the lower levels, but a few, including Nouguier, Compagnon, the President of the City Council and reporters from Le Figaro and Le Monde Illustré completed the climb. At 2.35 Eiffel hoisted a large French flag, to the accompaniment of a 25-gun salute fired from the lower level. There was still work to be done, particularly on the lifts and the fitting out of the facilities for visitors, and the tower was not opened to the public until nine days after the opening of the Exposition on 6 May: even then the lifts had not been completed. The tower was an immediate success with the public, and nearly 30,000 visitors made the 1,710 step climb to the top using the stairs before the lifts entered service on 26 May. Tickets cost 2 francs for the first level, 3 for the second, and 5 for the top, with half-price admission on Sundays, and by the end of the exhibition there had been 1,896,987 visitors.

After dark the tower was lit by hundreds of gas lamps and a beacon sending out out three beams of red, white and blue light using two mobile projectors mounted on a circular rail. The opening and closing of the Exposition were announced every day by a cannon fired from the top.

On the second level, the French newspaper Le Figaro had an office and a printing press, where a special souvenir edition, Le Figaro de la Tour, was produced. There was also a pâtisserie.

On the third level the was a post office, where visitors could send letters of postcards as a memento of their visit. Graffitists were also catered for: sheets of paper were mounted on the walls for visitors to record their impressions: these were replaced daily. Gustave Eiffel describes some of the responses as "vraiment curieuse"

Famous visitors to the tower included The Prince of Wales, Sarah Bernhardt, "Buffalo Bill Cody (his Wild West show was an attraction at the Exposition) and Thomas Edison. Edison was invited by Eiffel to his private apartment at the top of the tower, where Edison presented him with one of hisphonographs: this invention was one of the sensations of the Exposition. Edison signed theguestbook with the following message—

To M Eiffel the Engineer the brave builder of so gigantic and original specimen of modern Engineering from one who has the greatest respect and admiration for all Engineers including the Great Engineer the Bon Dieu, Thomas Edison.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years; it was to be dismantled in 1909, when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris. The City had planned to tear it down (part of the original contest rules for designing a tower was that it should be easy to demolish) but as the tower proved valuable for communication purposes it was allowed to remain after the expiry of the permit. Eiffel made use of his apartment at the top level of the tower to carry outmeteorological observations, and also made use of the tower to perform experiments on the action of air resistance on falling bodies.

Design of the tower

Material

The puddled iron (wrought iron) structure of the Eiffel Tower weighs 7,300 tonnes, while the entire structure, including non-metal components, is approximately 10,000 tonnes. As a demonstration of the economy of design, if the 7,300 tonnes of the metal structure were melted down it would fill the 125-metre-square base to a depth of only 6 cm (2.36 in), assuming the density of the metal to be 7.8 tonnes per cubic metre. Depending on the ambient temperature, the top of the tower may shift away from the sun by up to 18 cm (7.1 in) because of thermal expansion of the metal on the side facing the sun.

Wind considerations

At the time the tower was built many people were shocked by its daring shape. Eiffel was accused of trying to create something artistic without regard to engineering. However, Eiffel and his engineers, as experienced bridge builders, understood the importance of wind forces and knew that if they were going to build the tallest structure in the world they had to be certain it would withstand them. In an interview with the newspaper Le Temps (Paris) of 14 February 1887, Eiffel said:

Now to what phenomenon did I give primary concern in designing the Tower? It was wind resistance. Well then! I hold that the curvature of the monument's four outer edges, which is as mathematical calculation dictated it should be … will give a great impression of strength and beauty, for it will reveal to the eyes of the observer the boldness of the design as a whole.

Eiffel used empirical and graphical methods accounting for the effects of wind rather than a specific mathematical formula. Careful examination of the tower shows a basically exponential shape; actually two different exponentials, the lower section overdesigned to ensure resistance to wind forces. Several mathematical explanations have been proposed over the years for the success of the design; the most recent is described as a nonlinear integral equation based on counterbalancing the wind pressure on any point on the tower with the tension between the construction elements at that point. As a demonstration of the tower's effectiveness in wind resistance, it sways only 6–7 cm (2–3 in) in the wind.

Accommodation

When built, the first level contained two restaurants: an "Anglo-American Bar", and a 250 seat theatre. A 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) promenade ran around the outside.

On the third level were laboratories for various experiments and a small apartment reserved for Gustave Eiffel to entertain guests. This is now open to the public, complete with period decorations and lifelike models of Gustave and some guests.

Passenger lifts

The Fives-Lille lifts from ground level to the first and second levels were operated by cables and pulleys driven by water-powered pistons. The hydraulic scheme was unusual for the time in that it included three large counterweights of 200 tonnes each sitting on top of hydraulic rams which doubled up as accumulators. As the lifts ascend the inclined arc of the pillars, the angle of ascent changes. The two lift cars are kept more or less level and indeed are level at the landings. The cab floors do take on a slight angle at times between landings.

The principle behind the lift drive is the same as block and tackle, but in reverse. Two large hydraulic rams (over 1 metre diameter) with a 16 metre travel were mounted horizontally in the base of the pillar: this pushed a "chariot" with 16 large triple sheaves mounted on it. Six wire ropes were roved back and forth between the chariot and 14 fixed sheaves, so that each rope passes between the two sets of sheaves seven times. The ropes were then led from final sheaves on the chariot and led through a series of sheaves to the lift carriage. This arrangement means that the lift travels 8 times the distance that the rams move the chariot. The hydraulic fluid was water, normally stored in three accumulators, complete with counterbalance weights. To make the lift ascend, water was pumped using an electrically driven pump from the accumulators to the two rams. Since the counterbalance weights provided much of the pressure required, the pump only had to provide the extra effort. For the descent, it was only necessary to allow the water to flow back to the accumulators using a control valve. The lifts were operated by an operator perched underneath the lift cars. His position (with a dummy operator) can still be seen on the lifts today.

The Fives-Lille lifts were completely upgraded in 1986 to meet modern safety requirements and to make the lifts easier to operate. A new computer-controlled system was installed which completely automated the operation. One of the three counterbalances was taken out of use, and the cars were replaced with a more modern and lighter structure. Most importantly, the main driving force was removed from the original water pump such that the water hydraulic system provided only a counterbalancing function. The main driving force was transferred to a 320 kW electrically driven oil hydraulic pump which drives a pair of hydraulic motors on the chariot itself, thus providing the motive power. The new lift cars complete with their carriage and a full 92 passenger load weigh 22 tonnes.

Owing to the elasticity of the cables and the time taken to get the cars level with the landings, each lift in normal service takes an average of 8 minutes and 50 seconds to do the round trip, spending an average of 1 minute and 15 seconds at each floor. The average journey time between floors is just 1 minute.

The south pillar was fitted with an electrically driven lift in 1983 to serve the Jules Verne restaurant. This was supplied by Otis. A further four-ton service lift was added to the South pillar in 1989 by Otis to relieve the main lifts when moving small loads or maintenance personnel.

The east and west hydraulic (water) lift works are on display to the public in a small museum in the base of the east and west towers, which is somewhat hidden from public view. Because the massive mechanism requires frequent lubrication and attention, public access is often restricted. The rope mechanism of the North tower is visible to visitors as they exit from the lift.

Maintenance

Maintenance of the tower includes applying 50 to 60 tonnes (49 to 59 long tons; 55 to 66 short tons) of paint every seven years to protect it from rust. The height of the Eiffel Tower varies by 15 cm (5.9 in) due to temperature.

Aesthetic considerations

In order to give the appearance of uniform colour the paint used is graduated in tone to counteract the effect of atmospheric perspective, and is lighter at the bottom, getting darker towards the top. Periodically the colour of the paint is changed; as of 2013 it is bronze coloured. On the first floor there are interactive consoles hosting a poll for the colour to use for the next repaint.

The only non-structural elements are the four decorative grillwork arches, added in Sauvestre's sketches, which served to make the structure look more substantial, and to make a more impressive entrance to the Exposition.

One of the great Hollywood movie clichés is that the view from a Parisian window always includes the tower. In reality, since zoning restrictions limit the height of most buildings in Paris to seven storeys high, only a small number of taller buildings have a clear view of the tower.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

05:48

05:48

Planet Worldwide

Planet Worldwide

Posted in:

Posted in:

0 comments:

Post a Comment